Staving off the January Blues with The Death of Bunny Munro

Words by Isabelle Proctor

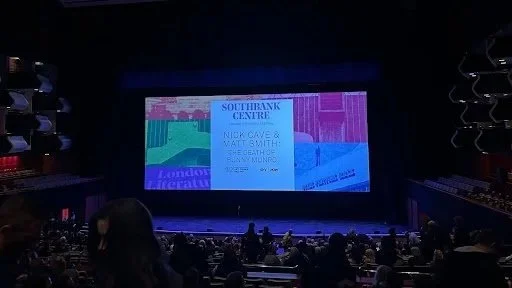

Fresh from the National Theatre’s Forza Wine, Tanya having tried a beetroot cocktail that the waiter only told us is very “divisive” as we were paying the bill, we sit down at the Southbank Centre to screen the first two episodes of The Death of Bunny Munro.

Like a good press ticket-holder, I read Nick Cave’s book in advance. For two weeks (I’m a slow reader, okay), my commute was contaminated with the degenerate narrative of Cave’s “travelling salesman” Bunny Munro. I bought a copy on eBay, the Canongate one with the horrorshow bunny costume on the front rather than the blond child with the toy gun. Unfortunately, it is between A4 and A5 with a much larger font than you would want for discreet reading.

Cave apparently hates Bukowski but you wouldn’t know that from his writing. His reimagining of Brighton and the Avon pyramid scheme (my own take, not confirmed by Cave) reads just like Tales of Ordinary Madness. After his wife commits suicide, Munro drives around Brighton, his son Bunny Junior in tow, seeking desperate and disturbed women to flog cheap cosmetics to - and have sex with. When rejected, Munro attacks his would-be customers.

Bunny is a sexual predator, bigot, and violent alcoholic. Morally repugnant, he is a dirty middle-aged man who has convinced himself, his son, and momentarily women that he’s a rockstar. He’s the sort of character who would enjoy listening to foxes mating and believes himself the best salesman in the whole world - a Stephen Bartlett confiscated of the podcast mic and armchair.

Bunny Munro’s recurring violent sexual fantasies about Kylie Minogue and Avril Lavigne required a certain display of pursed lips and feigned nonchalance in case the person next to me caught a glimpse of the filth I was reading. Drunken men, cramped train carriages, a vicious dog or a heavy meal made me think of Bunny.

The opening titles are predictably cinematic, the theme song written and performed by Nick Cave and a Bad Seeds bandmate Warren Ellis. You can’t help but think of Lana Del Rey as pastel pink cursive overlays a murmuration of starlings circling Britghton pier, backed by a moody ballad.

You know from the offset that Bunny is going to die, the title of the book - and TV series - is a deliberate giveaway. Both begin with Bunny and his wife looking out different windows at a fire in Brighton while news of a rampaging killer wearing devil’s horns blares on the TV.

Sarah Greene appears in an orange negligee (far classier than it sounded in the book) as Libby Munro; Bunny’s wife and Junior’s mother. Greene’s Libby is far more beautiful and stable than Cave’s. This has the effect of making Bunny’s incontinent libido and manipulation seem far less sociopathic.

I’m sure that Matt Smith would love to hear that he’s slightly too attractive to play Bunny - someone has probably already told him. Smith has experience playing several villains, from Damon Targaryen to Prince Philip, yet he still doesn’t quite embody the creepy, desperate loser with occasional (deceptive) charming moments. The hair and makeup department do manage to realise the curl on Munro’s forehead which I had dismissed as a nice but unwelcome suggestion from Cave when reading the book - a bit like when fantasy authors try to push skintight leather trousers.

Junior is also less tragic than in the books - his debilitating eye infection not playing such a central role. Nor does his intelligence, which apparently had to be diminished in order to increase his parents’ sex appeal. In the novel, after his wife’s funeral which he missed most of because he was having a wank in an outdoor toilet, Bunny focuses on Junior long enough to brag to his friends that he can name the capital of any country in the world. Junior is asked what the capital of Mongolia is and he replies Ulaanbaatar, though he pronounces it wrong - presumably because he has never heard it said aloud.

In the series, the moment is ruined even further as Bunny’s dim-witted acquaintances can only think to quiz Junior on the capital of England and then return to getting drunk and high once he successfully answers.

The inertia of the story is at odds with Bunny’s frenzy as he attempts to forget his wife’s suicide. Cave keeps Bunny moving, often drunk behind the wheel. Director Isabella Eklöf, who also directed Industry (which goes some way to explaining the depravity), realises how close Bunny actually stays to home, each estate and cul-de-sac another depressing corner of Sussex.

There are several Americanisms, which I had also dismissed when reading the book, that make the screening slightly jarring. Bunny addresses women as ‘Baby’ in the book which Smith’s acting makes all the more crass in the series. Similarly, Bunny Junior evolves from being largely nameless in his father’s eyes, occasionally referred to as Bunny Boy, to being permanently ‘Junior’. Book Bunny drives a Fiat Punto, series Bunny drives an open-top vintage American model. I get caught between the two.

After the screening, there is a short break - during which Eklöf smiles at us! - and then Nick Cave, Matt Smith and Edith Bowman come onto the stage. You can’t help feeling sorry for Edith Bowman as she tries to ask interesting and probing questions about both men’s creative processes while they stare down the barrel of a very long press tour.

Slightly otherworldly, Nick Cave is humble but seems reluctant to elaborate on his answers while Matt Smith looks at him the way Junior looks at Bunny. It would be fair to say that it seems both Cave and Smith have had a drink.

I’ve listened to Cave being interviewed by Bella Freud and Louis Theroux and he is difficult to pin down. I’m pretty sure he plucks the line “a new record” from thin air when Bowman asks him what he will write next. He really is the ‘70s rockstar-vampire his wife’s former fashion line painted him to be: cool, cultured, and tortured. Of course, this book and series are personal to Cave, having lost his son several years ago.

In this discussion he maintains that writing The Death of Bunny Munro was in response to a friend challenging him to write a story about a travelling salesman. Cave has written a screenplay before, only to be turned down and later asked if his novel could be adapted into a screenplay.

It’s hard not to romanticise The Death of Bunny Munro as Hemingway-Bukowski-Eugenides fan-fiction so that is what the series does. If that doesn’t convince you to watch it, I guarantee Bunny and his son are having a worse January than you.